People, Power, Poison, & Plastic

Contributors: Sakereh Carter and Dr. Sacoby Wilson

Image I. The shale gas fracking boom increased methane emissions, a greenhouse gas that’s 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Photograph: Andrew Burton/Getty Images

You are not intelligent and you don’t have the guts to speak truth to power. At least, that’s what the petrochemical industry believes. In fact, plastic manufacturers in the petrochemical industry apply the same formula to all consumer relations: (A) Treat everyone like passive mindless lemmings that care more about convenience and glossy new items than virtue, (B) Once their indiscretions become public knowledge convince us that we can make a difference by “remembering to recycle”, and after we’re drowning in plastic © make us feel like the problem is insurmountable, so that you don’t do anything about it. You CAN do something about it, but first you have to know the TRUTH. The truth is….the people in power are poisoning us with plastic.

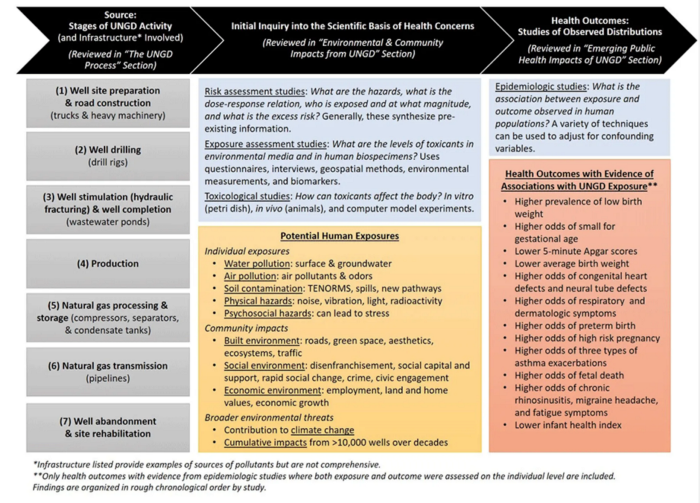

In order to understand the insidiousness of plastic, you have to understand how plastic is produced, distributed, and disposed of. Over 99% of plastic is produced from FOSSIL FUEL derived chemicals (See Image I) [1]. Fossil fuels are extracted from the Earth using a process termed hydraulic fracturing or “fracking”. Hydraulic fracturing is a laborious mechanistic process that utilizes high pressure water and a concoction of toxic chemicals to release oil and natural gas from beneath the Earth’s surface [2,3]. Fracking one site, requires 9.8 million gallons of water and fracking fluid contains more than 1,021 chemicals [2, 3]. Furthermore, hydraulic fracking requires 2,300–4,000 truck trips/well highlighting the impact of fracking activity on local air quality [4]. Fracking operations undermine low-wealth Black, Indigenous, and other individuals of color (BIPOC), as BIPOC homeowners often do not possess the mineral rights associated with their land [5]. A mineral right is the right to extricate natural resources, such as natural gas and oil or to accrue revenue from resource extraction on a parcel of land [5]. Mineral rights are a commodity that can be bought, sold, and traded. Typically, mineral rights supersede surface rights and without mineral rights BIPOC homeowners are susceptible to hyperlocal hydraulic fracturing operations [5]. In “Place-based perceptions of the impacts of fracking along the Marcellus Shale”, a resident of West Virginia details her experience with the fracking industry, “The major problem in West Virginia is we don’t have a say so. Landowners who have owned their property for hundreds of years never had to fight about being poisoned on their own property, but now somebody can come in and say, ‘We’re on your land, this is what we’re doing, sorry but we’ve got the right [5].” Furthermore, fracking operations plummet property values and affect place-based perceptions of community value among local residents [5]. Fracking operations can contaminate groundwater posing major health risks, as individuals may consume water containing chemicals associated with infertility, hormone disruption, cancer, birth defects, and asthma [6]. A comprehensive review of over 100 peer-reviewed articles revealed an association between fracking and adverse birth outcomes including low-birth weight, high-risk pregnancies, and developmental abnormalities (See Figure 1) [7]. A systematic review of hydraulic fracking conducted by Hayes et al., 2014 revealed that 84% of public health investigations identified health risks associated with fracking operations, 69% of water studies identified a high-risk or actual incidence of groundwater contamination, and 87% of air quality studies exhibited degradation of local air quality attributed to fracking procedures [8]. Thus, simply the extraction of materials necessary to synthesize plastic is dangerous for public health.

Figure I. Fossil fuel extraction and processing pipeline, exposure interface, and potential health outcomes related to the hydraulic fracturing process. Credit: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public

Johnston et al., 2016 demonstrated that low-wealth populations of color in Texas on the Marcellus Shale are disproportionately impacted by wastewater disposal associated with fracking operations [9]. Zwickl, 2020 analyzed fracking wells located in four U.S. states (Colorado, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas) and discovered that African-Americans were more likely to live in close proximity to fracking wells relative to other racial/ethnic groups [10]. From an environmental justice perspective, the distribution (where fracking wells are located) and procedural (who has the power to determine where fracking sites are placed) aspects of the fracking process are often unjust and discriminatory [11]. For example, community residents opposed to fracking procedures often experience ‘misrecognition’, a process by which community perspectives are perceived as subservient and the dominant discourse (narrative posed by the fracking industry) persists uncontested; thus, the concerns of community members are chronically overlooked [11].

Following fossil fuel extraction, fossil-fuel based materials are directed to petrochemical facilities and used to produce resins or “plastic nurdles” (See Image 2) [12]. Plastic nurdles are tiny balls of plastic with differential compositions that serve as the building blocks for a wide-range of plastic products including “milk containers, bottles for cleaning supplies, personal care items, fuel tanks, toys, piping, drums and buckets, grocery bags, car upholstery, home furnishing upholstery, and plastic covers [13].” Approximately, 60 billion pounds of nurdles are synthesized in the United States every year [14]. A research study conducted by Mato et al., 2001 analyzing resin pellets recovered from seawater discovered that plastic “nurdles” adsorbed toxic chemicals, such as polychlorinated biphenyls and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) that bioaccumulate (travel up the food chain) in marine species. Thus, humans may be consuming fish with high concentrations of toxic chemicals adhered to plastic resins [15]. Petrochemical facilities are disproportionately sited in BIPOC communities and adversely impact the health of local residents. In fact, a study conducted by researchers at the University of Texas School of Public Health revealed that children living within two miles of the Houston Ship Channel, the largest petrochemical complex in the United States, exhibited a 56% increased risk of developing leukemia relative to children living farther away from the port [16]. Local residents living near the Houston Ship Channel claim the air is heavy with foul-smelling chemicals that diffuse when you reach the outskirts of the city [17]. “I want to get out of here and go to the country and find some cleaner air,” said Eugene Barragan, an electrician that’s lived near the port for years. “It would be better for me and the kids.” Medical professionals have identified several benign albeit abnormal growths in his lungs, and he can’t afford to characterize the new growths [17]. “When I work hard, I start coughing and coughing and can’t stop,” he said. “I know a lot of people who have problems like that.” Dennys Nieto, a former resident of Houston, Texas said, “I suffer from asthma and pain in my lungs. It feels like I’m being hit in the lungs…Headaches, inflammation and pain in my throat. And also I have erratic blood pressure and heartbeat [17].”

Image 3. Residents of St. James Louisiana March against Death Alley on Oct. 23rd, 2019. Credit: William Widmer for Rolling Stone

In Louisiana, “Cancer alley”, an 85-mile stretch of land between Baton Rouge and New Orleans is riddled with over 150 petrochemical facilities and oil refineries [18].

Community members residing in Reserve, Louisiana, a community in “cancer alley” have a cancer risk 50 times higher than the national average [19]. “It is killing people by over-polluting them with toxins in their water and in the air,” he said. “This is slavery of another kind [20].” In 2018, the Formoso plant selected St. James Parish, another community in “Cancer Alley”, to host a 9.4 billion petrochemical complex that would double toxic emissions in the region (See Image 3) [21]. The proposed site will be constructed on a suspected burial ground for enslaved Americans [22]. In Hop Hopkins, the Sierra Club’s director of Strategic Partnerships article “Racism is Killing the Planet” he says: “When we pollute the hell out of a place, that’s a way of saying that the place- and the people and all the other life that calls that place home- are of no value…If our society valued all people’s lives equally, there wouldn’t be any sacrifice zones to put the pollution in. If every place was sacred, there wouldn’t be a Cancer Alley [23].”

Plastic Use

Image 4. “A man makes a heap of plastic bottles at a junkyard on World Environment Day in Chandigarh, India, June 5, 2018.” REUTERS / Ajay Verma

Using plastic may be toxic to your health. A small pilot study investigating the presence of microplastics in the feces of eight people from Finland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia, the United Kingdom and Austria identified microplastics in all stool samples, suggesting that humans are “pooping” plastic (See Image 4) [24]. Chelsea Rochman, an ecologist at the University of Toronto describes her reaction to the study’s findings. “I’d say microplastics in poop are not surprising….For me, it shows we are eating our waste….. mismanagement has come back to us on our dinner plates. And yes, we need to study how it may affect humans [25].” Researchers investigating the organs of 47 deceased individuals identified microplastics in the lung, liver, spleen, and kidneys of all subjects including polycarbonate (PC), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyethylene (PE), and Bisphenol A (BPA) [26]. Although, several studies have investigated the relationship between plastic pollution and health in marine wildlife, there’s a paucity of data related to plastic pollution and human health [27]. Thus, the biological implications of plastic pollution are unknown. Ingestion of plastic-laced food is not the only route of concern for humans. In fact, plastic chemicals may leach into groundwater at waste-receptor sites or landfills [28]. Moreover, in order to improve the malleability and versatility of plastic, manufactures often add plasticizers or phthalates to inflexible plastic materials that have been shown to exhibit reproductive toxicity (i.e. genital malformation in offspring, decreased sperm count, and fetal death) in male and female mouse studies [29]. According to Scientific American, 8 out of 10 babies and nearly all adults have some level of phthalates in their bodies [30]. Therefore, we have to make plastic more toxic just to retain its functionality.

Disposal of Plastic

Image 5. Smoke billows from an incinerator. Credit: Alfed Palmer

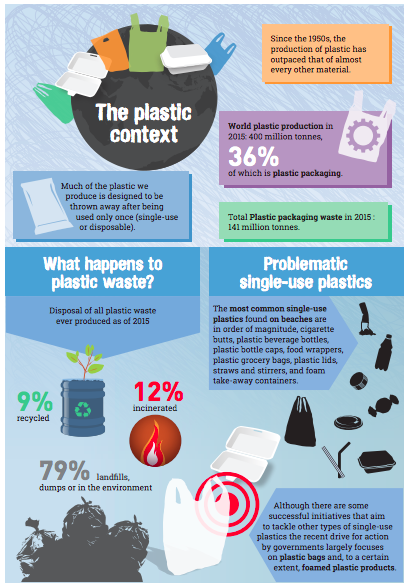

If you made it this far, your mind is probably reeling right now. You may be thinking of ways to decrease plastic use, such as recycling. Unfortunately, only 9% of all plastics discarded since 1950 have been effectively recycled [31]. Where is all of this plastic going? Approximately, 79% of our plastic waste ends up in a landfill, oftentimes in low-wealth BIPOC communities [32]. As ground litter, plastic takes approximately 1,000 years to decompose [33]. Plastic that is not recycled or directed to a landfill is incinerated. In 2017, approximately 13.2% of plastic waste was incinerated in America (See Image 5) [34]. Out of the 73 incinerators in the U.S., 79% of these facilities are located in BIPOC communities [35]. However, there are only so many BIPOC communities in America and we have an image to uphold. To perpetuate the fallacy of “American innocence”, “the land of the free”, “the American dream”, and “American superiority”, the petrochemical industry keeps the sheer amount of plastic out of our immediate environment, a type of “outta sight, outta mind” approach to waste management. If you woke up next to a mound of foul-smelling deteriorating plastic every single day, your image of America would not only wane but you’d yearn for the opportunity to see crystal blue skies and greenery. In fact, you’d want to do something about the insurmountable amount of plastic waste. The petrochemical industry can’t have that, so you must be ignorant to the overwhelming level of plastic waste and ignorant to the horrific experiences of people that are dying at the hands of it’s consumption. How does America retain this image? We export our garbage to other low-wealth BIPOC communities outside of America.

Image 6. Plastic debris accumulates in Malaysian waterbody near an illegal recycling factory

In 2018, China implemented the National Sword Policy which legally repudiated plastic exports from American shores [36]. Following implementation of the National Sword Policy, we began exporting our plastic waste to countries in Southeast Asia including Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand (Image 6) [31]. Southeasian countries do not have the capacity nor technology to properly dispose of plastic waste. Thus, several plastic receptacles in Southeast Asia revert to “open-air burning” plastic trash, in a futile effort to decrease the inordinate amount of plastic material [37]. Open-air burning releases a myriad of toxic substances including dioxins, furans, mercury, and polychlorinated biphenyls into the air [37]. In Thailand, a country with lax environmental regulations and a major receptor site for America’s plastic waste, a resident describes her perception of Americans. “You are selfish…Don’t push the trash out of your country. It’s your trash and you know it’s toxic…Why do you dump your trash in Thailand?” [31]. Open-air plastic burning can contaminate local waterways and streams; therefore, plastic pollution has rendered her drinking water unsafe. In Jenjarom, a small town in Malaysia, Chinese businessman touted the arrival of economic investment, a front for the illegal waste industry business [31]. Soon after the arrival of ‘economic investment’, community members complained of respiratory problems and rashes attributed to the open-air burning of plastic [31]. “If you don’t die…it goes on and on and you have to go to the doctor and pay money.” Electronic waste or e-waste also poses a major health risk to local residents in Southeast Asia. Often, Southeasian communities open air burn “ plastic casings of electronic equipment, circuit boards, and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) coated wires [31].” Burning of plastic casings releases highly-toxic chemicals including dioxins, brominated flame retardants, lead, cadmium, chromium, and polychlorinated biphenyls which are associated with immune toxicity, reproductive dysfunction, and cancer [31]. Out of the 450 million metric tons of e-waste that we’ve produced, only 20% has been effectively recycled [31].

Image 7. Two African-Amerian/Black fists break free from mental and physical slavery. LysenkoAlexander

Slavery was not abolished in 1865, it was simply reconstrued or reconfigured to look less overt or conspicuous. Environmental slavery is a term that denotes (a) the disproportionate siting of toxic facilities in low-wealth BIPOC communities, (b) political disenfranchisment of low-wealth BIPOC, © barring of social mobility attributed to social and environmental degradation, (d) the perceived inferiority of low-wealth communities of color which justifies place-based environmental degradation, and (e) a complete disregard for BIPOC lives (Image 7) [38]. Analagous to slavery in America, we exploit low-wealth BIPOC to withstand and soakup highly toxic substances, treat BIPOC individuals as 3/5ths of a human, nurture socio-environmental “bondage” that prevents BIPOC individuals from accumulating economic wealth and the ability to flee toxic neighborhoods, devalue low-wealth BIPOC neighborhoods in order to justify the inhumane aggregation of toxic facilities and state-sactioned poisoning, and execute biological onslaught in BIPOC communities because we don’t care whether they live or die. Environmental inequity is not for the “greater good”, we don’t have to sacrifice one group of people to benefit another. We have the power to create a just, equitable, and morally sound society. Akin to slavery in America, if you didn’t speak truth to power, you are indirectly upholding this iniquitous system.

Revenue stream

Over the next decade, the petrochemical industry plans to spend $47 billion to increase the scalability of plastic production [39]. The global market value of petrochemicals is projected to increase to $651.1 billion US. dollars by 2027 [40]. According to the International Energy Agency, the petrochemical industry will account for 50% of fossil-fuel demand by 2050 (See Figure 2) [41]. In a report by the Center for Constitutional Rights, the document states “conservative and corporate interests have captured our political process to harness profit, further entrench White supremacy in the law, and target the safety, human rights and self-governance of marginalised communities [42].”

Figure 2. HIstorical data and projections to 2050 of plastic waste production and disposal. “Primary waste” is plastic becoming waste for the first time and doesn’t include waste from plastic that has been recycled. Source: sciencemag

Solutions

We have the power to change the way society operates, a society that allows us to live together harmoniously and peacefully, free of injustice. Let’s focus on environmental solutions that address the root of the problem, not just the symptoms. The Community Engagement, Environmental Justice, and Health (CEEJH) lab provides a list of recommendations compiled from various sources to address the plastic pollution crisis.

Infographic 1. United Nations Environment Programme Single-Use Plastic Sustainability Factsheet. Source: UN Environmental Programme

No more single use plastic items!: Cease the production of single-use plastic items. A report by Greenpeace revealed that most single use plastic items produced in America are non-recyclable (See Infographic I) [43]. In fact, most single use plastic items end up in landfills or as plastic litter. Single use plastic items include cigarette butts, plastic beverage bottles, plastic bottle caps, food wrappers, plastic grocery bags, plastic lids, straws and stirrers, and foam containers.

Implement policies that curb plastic pollution: The Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act of 2020 brought forth by Senator Tom Udall (NM) and Rep. Alan Lowenthal (CA) tackles the plastic pollution crisis from a legislative standpoint [44]. The Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act (a) requires that companies are fiscally responsible for recycling or composting plastic waste AFTER consumption, (b) starting Jan 1st, 2022 the bill phases out all single use plastic items, © requires that companies are transparent about which items are recyclable and non-recyclable, and (d) places a moratorium on the expansion of petrochemical facilities until the EPA establishes a robust waste management plan [44].

Zero waste initiative: Implement a zero waste initiative in your local community. According to the Zero Waste International Alliance, Zero waste is defined as “the conservation of all resources by means of responsible production, consumption, reuse, and recovery of products, packaging, and materials without burning and with no discharges to land, water, or air that threaten the environment or human health [45].”

Plastics and Human Health: Conduct more research on the impacts of plastic on human health [46]. Researchers have extracted microplastics from over 114 marine species, and 33% of these microplastics are ingested by consumers of fish [47]. A study conducted by Vandenberg, 2011 analyzing Bisphenol A (BPA) in plastic packaging found that 95% of Canadians contained some level of BPA in their bodies [48]. An investigation conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) analyzing the amount of microplastics across 259 water bottle brands found that 90% of the tested water bottle brands contained microplastics (See Figure 3) [49]. Additionally, a report published by Orb Media discovered that 94% of tap water in America contained microplastics [50]. The Global Apparel Fiber Consumption revealed that approximately 70% of synthetic fibers, a type of plastic, are used in clothing apparel [51]. Synthetic fibers are derived from fossil fuels and these microplastics are released from our clothing everyday. Typically, synthetic fibers are combined with toxic chemicals that are absorbed by the skin. In fact, research has shown the synthetic fibers can cross the blood-brain barrier, a natural bodily barrier that prevents harmful substances from entering the brain [52].

Figure 3. Researchers identified microplastics in 11 different water bottle brands, with an average concentration of 325 microplastic particles per liter of water.

SPEAK TRUTH TO POWER: One life is not more valuable than another. We all deserve to live in a clean, healthy environment. Every action counts, if you’re interested in ameliorating global plastic pollution (a) join anti-plastic coalitions, (b) collaborate with green groups, (c.) work with frontline communities, (d) VOTE on anti-plastic legislation, and (e) join social justice groups including the NAACP. Below, the CEEJH lab has provided a list of organizations, groups, and policies that readers can support and/or join.

Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA). GAIA seeks to “catalyze a global shift towards environmental justice by strengthening grassroots social movements that advance solutions to waste and pollution. We envision a just, zero waste world built on respect for ecological limits and community rights, where people are free from the burden of toxic pollution, and resources are sustainably conserved, not burned or dumped”. Check out GAIA’s discarded report on global plastic pollution [53]!

Clean Water Action (CWA). Clean Water Action aims to “get health-harming toxics out of everyday products; protect our water from dirty energy threats — drilling and fracking for oil and gas, and power plants pollution; build a future of clean water and clean energy; and keep our clean water laws strong and effective to protect water and health.” Check out plastic pollution solutions from CWA’s website [54]!

Join the Plastic Pollution Coalition. The mission of the plastic pollution coalition “is a global alliance of more than 1,200 organizations, businesses, and though leaders in 75 countries working toward a world free of plastic pollution and its toxic impact on humans, animals, waterways, oceans, and the environment [55].”

Image 8. Plastic pollution initiatives implemented in other countries.. Source: National Geographic

Policies

Support the congressional bill “Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act” introduced by Senator Lowenthal (D-CA) [44]. The Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act “makes certain producers of products (e.g., packaging, paper, single-use products, beverage containers, or food service products) fiscally responsible for collecting, managing, and recycling or composting the products after consumer use.” Watch the Story of Plastic [56]!

National Geographic provides a list of former plastic pollution initiatives (See Image 8) [57].

References

https://www.ciel.org/issue/fossil-fuels-plastic/#:~:text=Over%2099%25%20of%20plastic%20is,in%20the%20US%20and%20beyond;https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/aug/14/fracking-causing-rise-in-methane-emissions-study-finds

Thurka Sangaramoorthy, Amelia M. Jamison, Meleah D. Boyle, Devon C. Payne-Sturges, Amir Sapkota, Donald K. Milton, Sacoby M. Wilson, Place-based perceptions of the impacts of fracking along the Marcellus Shale, Social Science & Medicine, Volume 151, 2016, Pages 27–37, ISSN 0277–9536, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.002

Environmental Health Concerns From Unconventional Natural Gas Development Irena Gorski and Brian S. Schwartzhttps://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.44; https://www.ehn.org/health-impacts-of-fracking-2634432607.html

Hayes J, De Melo-Martín I: Ethical concerns surrounding unconventional oil and gas development and vulnerable populations. Rev Environ Health 2014, 29:275–276.

Johnston, J. E., Werder, E., & Sebastian, D. (2016). Wastewater Disposal Wells, Fracking, and Environmental Injustice in Southern Texas. American journal of public health, 106(3), 550–556. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.303000

Zwickl, Klara, 2019. “The demographics of fracking: A spatial analysis for four U.S. states,” Ecological Economics, Elsevier, vol. 161(C), pages 202–215.

Kroepsch, A. C., Maniloff, P. T., Adgate, J. L., McKenzie, L. M., & Dickinson, K. L. (2019). Environmental Justice in Unconventional Oil and Natural Gas Drilling and Production: A Critical Review and Research Agenda. Environmental science & technology, 53(12), 6601–6615. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b00209

https://www.alleghenyfront.org/ever-hear-of-a-nurdle-this-new-form-of-pollution-could-be-coming-to-the-ohio-river/; http://www.maskmagazine.com/the-swamp-issue/life/the-hidden-struggle-of-louisianas-cancer-alley

https://web.archive.org/web/20080420095307/http://healthebay.org/currentissues/ppi/bills_AB258.asp

https://myplasticfreelife.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/07/Moore-Plastic_Resin_1_1.pdf

https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/Study-Children-living-near-Houston-Ship-Channel-1544789.php (find original study)

https://gov.louisiana.gov/news/sunshine-project; https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/louisiana-cancer-alley-getting-more-toxic-905534/

https://www.sierraclub.org/articles/2020/07/deep-injustice-plastic-pollution

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/health/microplastics-human-stool.html; https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/health/new-study-finds-humans-are-ingesting-plastic-particles-in-food-1.783356

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/10/news-plastics-microplastics-human-feces/

https://www.greenmatters.com/p/microplastics-detected-human-organs

Sigler, M. The Effects of Plastic Pollution on Aquatic Wildlife: Current Situations and Future Solutions. Water Air Soil Pollut 225, 2184 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-014-2184-6; Erren, T., Zeuß, D., Steffany, F. et al. Increase of wildlife cancer: an echo of plastic pollution?. Nat Rev Cancer 9, 842 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2665-c1; Teuten, E. L., Saquing, J. M., Knappe, D. R., Barlaz, M. A., Jonsson, S., Björn, A., Rowland, S. J., Thompson, R. C., Galloway, T. S., Yamashita, R., Ochi, D., Watanuki, Y., Moore, C., Viet, P. H., Tana, T. S., Prudente, M., Boonyatumanond, R., Zakaria, M. P., Akkhavong, K., Ogata, Y., … Takada, H. (2009). Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 364(1526), 2027–2045. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0284

https://wastetradestories.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Discarded-Report-April-22.pdf; https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46518747

https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/plastics-material-specific-data#:~:text=In%202017%2C%20plastics%20generation%20was,measure%20the%20recycling%20of%20plastic; https://www.mancunianmatters.co.uk/news/25032014-poisonous-gas-levels-around-trafford-are-shocking-and-breach-eec-legal-limits-claim-pollution-protest-group/

Toxic Pollutants from Plastic Waste- A Review Rinku Verma , K. S. Vinoda, M. Papireddy, A.N.S Gowda

Environmental Justice Movement: A Review of History, Research, and Public Health Issues.Source: Journal of Public Management & Social Policy . 2010, Vol. 16 Issue 1, p19–50. 32p. 2 Charts, 1 Graph. Author(s): Wilson, Sacoby M.; https://www.istockphoto.com/illustrations/breaking-chains

https://www.hydrocarbonprocessing.com/magazine/2019/march-2019/trends-resources/business-trends-petrochemicals-2025-three-regions-to-dominate-the-surge-in-petrochemical-capacity-growth; https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/07/next-30-years-we-ll-make-four-times-more-plastic-waste-we-ever-have#:~:text=If%20these%20trends%20continue%2C%20by,the%20end%20of%20the%20millennium.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/dec/02/alec-white-supremacy-conservatives-racism

https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/the-myth-of-single-use-plastic-and-recycling/; https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/25523/singleUsePlastic_sustainability_factsheet_EN.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/5845

https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2020/03/reducing-plastic-pollution-in-the-oceans-and-beyond

https://www.whatsorb.com/news/microplastics-can-be-moved-from-the-ocean-is-it-harming-us

Vandenberg L. N. (2011). Exposure to bisphenol A in Canada: invoking the precautionary principle. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne, 183(11), 1265–1270. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101408

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/mar/15/microplastics-found-in-more-than-90-of-bottled-water-study-says;https://www.statista.com/chart/13255/study-finds-microplastics-in-93-of-bottled-water/#:~:text=In%20one%20case%2C%20a%20bottle,from%20Bisleri%2C%20Gerolsteiner%20and%20Aqua.

Seltenrich N. (2015). New link in the food chain? Marine plastic pollution and seafood safety. Environmental health perspectives, 123(2), A34–A41. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.123-A34

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/07/ocean-plastic-pollution-solutions/